THE INTERVIEW

Louise Covillas

1. Could you share a bit about your background and what led you to start your art practice?

I never had a specific moment when I realized I wanted to be an artist. I’ve always been creative, handy, and crafty for as long as I can remember, but I had no idea that you could actually study to become one. I think I had a very romanticized vision of the artist as a genius suddenly struck by inspiration, where everything comes from talent rather than hard work.

I think I was immersed in that idea, and when I learned that art could actually be studied, I realized that it was what I wanted to do. I ended up attending several art schools in different countries—three or four in total—which turned out to be a really interesting experience. I studied in Lisbon, Brussels, and finally Paris, and it was incredibly enriching because art studies are difficult to define. The experience varied greatly depending on the country, the school, and the institution. And honestly, how do you even put grades on something like art ?

2. What themes does your work explore?

Well, obviously, I’ve gone through different phases, but for the past few years, my work has revolved around the idea of collecting—gathering and reassembling things. Whether it’s a dead butterfly on the street or a beautifully textured piece of paper, I always feel the need to take things with me. That collection is my starting point to create.

The thing is, when you're collecting, you don't just stumble upon things by accident. You really have to adopt a mindset of attention. I don’t find things—I actively search for them. It’s a specific time dedicated to searching, and you always have to be in a heightened state of alertness. You have to be able to sniff things out, and that's how you start noticing these elements. So, it’s also about practicing awareness, and I think this awareness is what drives my work. It's through the attention I bring to everyday life that I’m able to create.

But it’s not just about objects—it’s also about people’s attitudes or finding poetry in everything. I really work with everyday life because it’s right there. There’s so much material to draw from, so why not use it?

3. How has your work evolved over the years, and what has influenced these changes?

I think the schools I attended really had a significant influence on me. Now that I’m out of school, I’m excited to see where it will take me, and I already feel a shift. When I was in Brussels, I worked a lot with large installations and multimedia videos. Then, when I moved to Paris, my work became much more conceptual. At that point, my pieces hardly had any material existence. Over time, though, I found myself returning to sculpture, and that was really helpful. I felt a bit stuck during those conceptual, abstract moments—it felt limitless, but also kind of limiting at the same time.

I’m really happy that I’ve been able to return to working with volume, and now that I’m out of school, I’m still very much into sculpture. But what’s different now is that I’m much more instinctive in my approach. I follow my instincts and desires, and it feels like there’s less pressure to conform to any particular structure.

4. Where do you find inspiration for your work?

In everyday life as I mentioned earlier but also when I step outside of my usual routine. My dad is from the South, so I often go there, and I really connect with that part of France. It’s a place where I can leave my daily life behind and have more space to open up, to be in that awareness. In that environment, I’m able to collect many things. For example, I’ve collected a snakeskin, a cicada chrysalis clinging to a sprig of lavender, butterflies, and bones from various animals. I even have a whole set of flamingo bones crystallized in salt.

When I’m there, it’s not really a holiday. I still use the time as a moment to create and absorb. And, of course, a lot of my inspiration comes from theory. I read a lot, and I have all my books there. For example, I have works by Marielle Massé, Baptiste Morisot, Phillipe Rahm or Ursula K. Le Guin, among many others.

I relate a lot to Massé's writing, as she uses personal, poetic, scientific, and sociological references all at the same level, with no hierarchy. That’s what allows—I think—her to have such a beautiful, higher view on things.

Q: Would you say your work is like a diary of your life and all these little things you collect?

Not really, no. My work is actually never really about me. Well, it’s always a bit about you, but more so, I have a body of work that focuses on cohabitation—on how we all coexist together. It’s about how, as humans, we often fail to realize just how intertwined we are with other living beings, and all the reflections that arise from that.

When I’m collecting elements, most of the time it’s natural things like shells, wood, and other similar items. It’s also a way to show that if you look closely enough, if you pay enough attention, you’ll realize you’re not alone. You know, you have this romantic idea of nature, like in Caspar David Friedrich's painting Wanderer above the Sea of Fog, where the human stands alone, facing nature. But in reality, you’re never alone in nature; it's buzzing with life.

My work is more about that—collecting traces, as Baptiste Morisot wrote in his book On the animal trail. The book shows us how we don’t look enough for these traces. If we paid attention, like I do when I collect, we’d notice that we’re not alone on these paths. There’s also an interesting concept called desire paths. Sometimes, urban planners discover small paths that form beside the roads they’ve designed. These paths emerge over time, through repeated steps, whether from people or animals. They don’t follow the planned routes; they form gradually through the accumulation of traces, showing a spontaneity that breaks free from the rules of planning.

These traces, especially those left by animals, actively contribute to creating these desire paths, which evolve and change over time. In a way, these paths represent a kind of intuitive navigation—an instinctual route that doesn’t adhere to structure but instead follows the flow of desire. This intuition, like in the creative process, guides my work. The desire to create, much like these desire paths, forms gradually over time, following a less structured path and responding to what emerges along the creative process.

5. Can you walk us through your creative process and how you bring an idea to life?

I always start with a process of collection and awareness. It’s all about creating mental space to collect things, whether they’re objects or thoughts. I really like the metaphor of a pocket for this. I even created a work based on the concept of pockets. I try to have enough mental space to gather elements, and in a way, I keep them in my pockets. I love Ursula K. Le Guin's image of the pocket— the more pockets (or attention) you have, the more you can collect. It’s like a metaphor for your mental space, being open to receiving and going through a collection process.

I often have very instinctive ideas. The process can be long because making decisions is hard for me—like which material to use, which dimensions to choose. But I’m always sketching my overall idea of the project. One thing I’ve noticed is that my sketches are often very close to the final object.

I think I’m really instinctive; I’ll have a vision for how I want it to look, and then it ends up looking just like that. But then I tend to focus more on the exact dimensions and the details—how to make the structure hold together, how to make it stand. I think I’m more meticulous with the details. I always have work that’s really focused on the details. I think it’s important. I can easily picture the overall idea, but then I really need time to process all the details, and that part takes much more time, actually.

6. What is the project you’re most proud of to date?

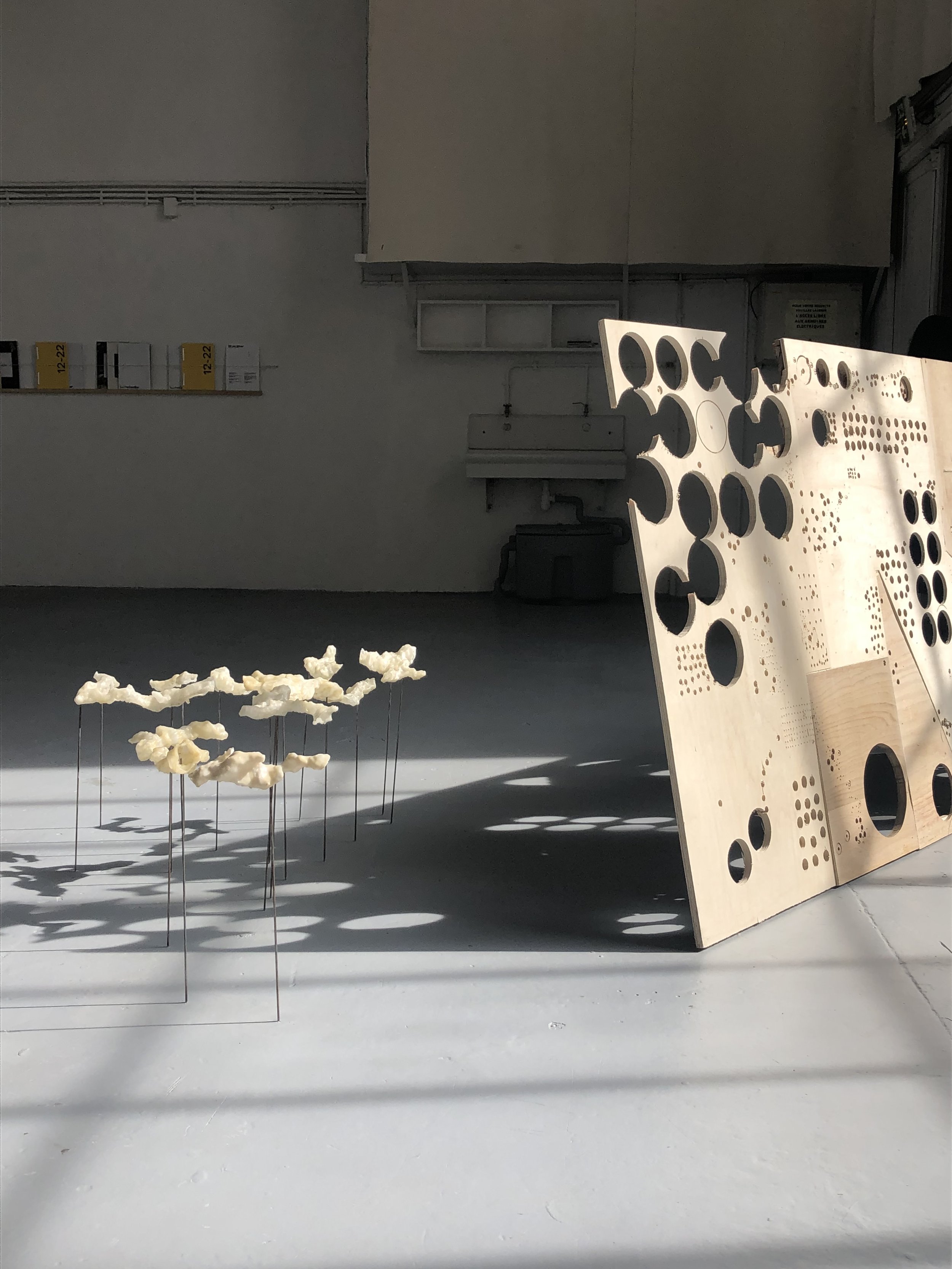

I think my graduation show, Till We Bloom, was my most complete work. It was a bit of a crazy project, because usually for your final exhibition, it's supposed to be your solo show—your chance to showcase your individual work. But I decided to make it a collaborative project and work with several artists.

It was a bit tricky at the start, but I’m really happy I did it because it was incredibly enriching to work with other artists. It was the same idea of the awareness and attention you bring to each other, tied to the concept of cohabitation. It made perfect sense to work with others, because cohabitation is all about engaging with others, both humans and non-humans.

I’m also really happy with how the show turned out. Working with others pushed me out of my comfort zone. I had to engage with their work, navigate their tastes, and understand each of their different creative processes. But it also gave me the opportunity to explore a wide range of materials, some I’d never used before, and different ways of producing or thinking. It was a beautiful collective moment.

7. Do you see yourself staying in Paris long-term, or are there other cities that inspire you to work there?

I enjoy doing residency boards. Of course, I always go to the South, and maybe one day I’ll live there, but for now, it’s really Paris for me, for several reasons. First of all, because so much of the culture happens here. I’m someone who needs that kind of stimulation—I need to see exhibitions all the time, I need to encounter new things.

I need to be aesthetically and visually stimulated. It’s the same as working with others and being influenced by them—I really need that. People often say that someone has been inspired by them or taken something from their work, but I believe we all inspire each other, and that’s so important. It’s essential to let that flow, to recognize how we all influence one another. This happens all the time in Paris, with all the exhibitions and the vibrant young art scene. My friends and I are always coming together to do exhibitions, to share work—it’s all about spontaneity, but it still comes with that collective spirit.

And of course, there’s also a really simple, practical reason for being in Paris. For me, it’s easy to find a side job, which is crucial. We don’t talk enough about the financial strain of being an artist. There’s a huge financial burden, especially when it comes to collecting materials. It’s something that can be really stressful, so knowing that I can find these resources and support in Paris is a big reason why I want to stay.

8. What would you like to accomplish in the next few years?

I think this is the trickiest question ever. I really enjoy collective projects, partly because being an artist is such a lonely practice. You don’t have a fixed schedule, and that can be isolating. I also think it’s super important not to be alone in your practice because when you're by yourself, you can get stuck on simple questions that would be resolved in a second if someone else was around. Sometimes, you just need to ask someone, "This one or this one?" and the answer comes so much easier.

So, I think collaboration, collective work, and still collecting are all part of my process. I don’t really see myself in one specific place or situation. I just hope it keeps evolving like this.

9. If there’s one thing you hope people take away from your work, what would it be?

I don’t think, as an artist, that you create for yourself. Well, maybe some people do, but I think it’s quite selfish. From the moment you show your work, it’s for others, and you just have to let it go.

When people see it and have a reaction, whether it's something like, “oh, it’s beautiful” or “that’s an interesting material”, those simple, basic thoughts are enough. As long as something happens in their mind, I’m glad. I don’t need you to understand my entire body of work, and I don’t expect you to. That’s not the point.

That’s also why I aim for a soft aesthetic in my work. I keep it quite sober, so it can be filled with the emotions or impressions of the viewer. Ultimately, it’s completely up to them.

There’s also the tricky question of whether you need an art education to understand art. I don’t think so. I wish more people would create with the consideration that not everyone shares the same cultural or social background.

That’s why I make sober works—so people can fill them with their own interpretations and perspectives.