THE INTERVIEW

Chloé Menous

1. Could you share a bit about your background and what led you to start your art practice?

I grew up in the Parisian suburbs, and I've been drawing and painting in my room since I was a teenager. After high school, I did humanities studies because I really felt drawn to texts, novels, and philosophy—how they can help you emotionally relate to the world and understand our intimate relationships to social and political structures. But the way we studied those texts felt really methodical and cold, far from my own sensibility.

So I changed direction and took the entrance exams for Beaux-Arts de Paris, where I felt much more free to use a changing language and do things at my own pace. I think this interest for text and language was really present in my work at first, and it slowly shifted to other forms.

2. What themes does your work explore?

I don't know if there's really a theme. I feel like it's fluctuating and changing, but maybe I'd say, in all my pieces, I work around the relationship we have to our environment and ourselves, and what symbolic bias may exist there. Now I'm really interested by the relationship we have with our daily environment—how it’s built and its history—like how cities are organized and what place plants and vegetal beings have in it, what relationship the urban territory allows us to develop with non-human beings. I'm working on the ambiguity there is between the representation of these vegetal beings, how they are fantasized or considered as ornamental and the way they are actually treated—often controlled or restrained.

This contrast really interests me—it can be very contradictory and translates a kind of tension.

Plants can be considered dirty but, at the same time, appealing. They are subject to control and cultivated, but also associated with an idea of wilderness. It echoes with the representation of the feminine body in a way, and how it exists in social space.

So, for me, working with the representation of vegetal beings is also a way to talk about intimacy and feelings related to the human body, to get closer to more subjective emotions.

Recently, I feel like my work is shifting to something else. I’m taking more and more interest in consumer objects, advertising methods… interiors also.

Q: When you say that your work is exploring the female body, do you use plant life as the personification of that in your work?

I think yes—in some of my pieces, the plants resemble the body. For example, in the big ceramic tulips named Toujours au mois d'août, which means “always in the August month” and refers to a precise breed of tulips represented in Dutch vanities, I used roots on the surface that trace veins on the petals, so they become a bit more like a body. The colors are also really reminiscent of the tone of skin or blushing cheeks.

In another piece I made that is named Be My Tutor, vegetal shapes on a metallic structure kinda start resembling spines or skeleton, and there are fruits I molded in the farm I worked in during the summer because they really looked like organs, laying on the ground—they are made of silicone and covered with my own makeup.

So, I feel like we can say there is some sort of metaphorical link between these shapes and the feminine body. This comparison is a really convenient way for me to talk about intimacy without representing it directly; to evoke physical feelings and maybe create a connection between the vegetal and human bodies—some sort of sensorial meeting place.

Q: Do you grow the plants you use in your work yourself?

In the pieces where I used real plants—for example, in the Wallpaper bas-reliefs or other ceramics—it was fallen plants I collected in parks, gardens, woods. I put clay on them, they burn and the clay preserves their form, containing their ashes. Or for the bottles titled Prairie, that contain brewing and decomposing plants, I recuperated them from a communal city garden I sometimes got to on the weekends. They were torn off because they were considered bad weeds.

But otherwise, I use molds or pre-existing figures; I model or draw their forms.

3. How has your work evolved over the years, and what has influenced these changes?

I'd say I introduced a sculptural part into my work—being able to experiment with new materials and facilities. Maybe it's also because I started working with representations of the vegetal—I felt the need to create presences that resemble those bodies. Sculptures and installations have a way to exist in the real world, spatially—they can reside in it, parasite it, you can meet with them on a corporal level, and this really interested me. I also continued working with bi-dimensional representations, like drawings, and it's really a different point of view—you kind of enter an extra-physical perspective. Introducing sculpture allowed me to work with those two ways of perception, and I really enjoy building in space through those contrasted ways, making them interact.

Also, when I started working, I regarded intimacy more through questions of language and symbols. I went a few years ago to Bretagne, where I spent a lot of time surrounded by plants. I started drawing them, and I did performances where I was letting myself be submerged by the sea. I think it was at that moment that I started feeling like working with vegetal beings and representing them.

It was something I already felt attracted to before, but it took me some time to get there. My mother, being a climatologist, I grew up being immersed in a really politicized environment around climate change and ecological questions, which can feel a bit suffocating... But then, I just felt really well in that place. At first, it was making really literal representations of plants and landscape. Then, going back to Paris for work and studying, I mostly experienced the absence of these plants, so I started concentrating myself more on their representation—the imagination there is around it. I started diving into that matter, and my work evolved alongside this interest.

4. Where do you find inspiration for your work?

I think I'd say mostly in places.

Working around non-human beings, I started seeking opportunities to be in places where they existed. I go a lot in parks and gardens—and I look at how plants are arranged and ordered. I started spending time in that communal garden, and working at a farm in the summer—that's where I molded or collected a lot of plants. It’s a really wonderful place in the south of France, filled with amazing people. These are places where I also found typologies of forms that insert into my practice—tutors used in agriculture, for example, or the way plants in gardens or in fields create repetitive patterns.

What interests me a lot in those places is how our human environments are constructed, architectured. Some of my pieces were really influenced by Art Nouveau architecture and design, and I looked a lot at Victor Horta’s work. His designs were inspired by plants. In my Wallpaper pieces, I reinterpret those forms. It’s like rewriting a rewriting of vegetal forms—if it makes sense—like a reversed way of making archeology, adding layers instead of uncovering them.

A few months ago, I was really into Middle Age tapestries depicting landscapes. Right now, I’m really interested in how supermarkets and shops are organized and looking at case study houses for their geometry.

Also, when I work, I listen to a lot of ambient music and I let myself be guided by the rhythms and sounds. I think rhythm, order, and disorder—that I can find an echo with in music—are really important in my practice and how, formally, it's composed.

Otherwise, I read a lot of science fiction books, and I look at a lot of drawings these days. I'm a bit obsessed with an artist named Adolphe Wölfli—I really love looking at his drawings. The same goes with the archive of Nancy Lupo’s exhibitions. I like how she composes in space, as if she were creating emotional landscapes.

5. Can you walk us through your creative process and how you bring an idea to life?

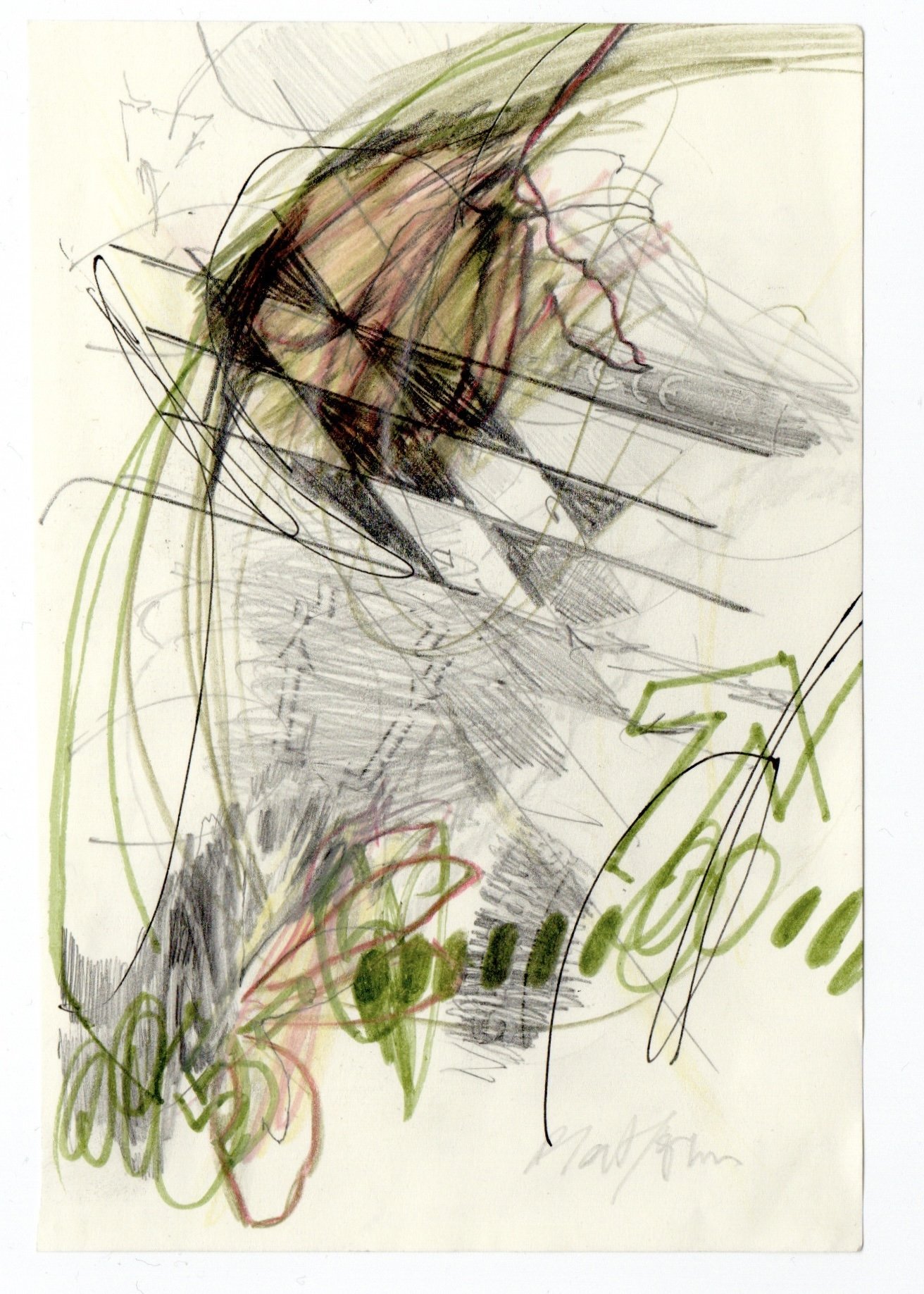

I would say it’s a bit intuitive. But what I can say—usually I think I take interest in some existing forms, and I start drawing other forms extrapolated from them. I start most of my sculptures from drawing. Then, I don't necessarily know how it’s going to evolve.

I think I'm really guided by the gestures and materials while making the pieces; they kind of lead me into a narrative. For example, for the series of sculptures I was making recently, I realized all the gestures I was making were a way of restraining the vegetal forms, exercising a form of authority, and at the same time composing some sort of harmony. The gestures were either reordering and creating an artificial plant out of the many species I molded, or enclosing plants into the clay, covering them with layers and layers of paint, or forcing them to follow some decorative shapes using plastic hose clamps.

6. What is the project you’re most proud of to date?

I think of the piece titled Be My Tutor. It's a structure made out of metal, inspired by tutors from agriculture. It’s a human-sized piece—one can go inside—but at the same time, it feels a bit like a defensive architecture to me. And it’s a place inhabited by plastic plants that follow really decorative metal shapes. For me, those plants are restrained and, at the same time, protected by the structure.

I feel a form of intimacy with this piece. To me, it raises questions of care and protection, attraction, and repulsion, which can make me really emotional. Also, friends helped me while doing it, so it reminds me of happy moments. And I felt like It was the first time I really managed to make the spontaneous composition logic I use when drawing happen in a sculpture—I felt a balance between technicity and improvisation.

It was also very fun simulating pistils by putting pollen on anti-pigeons spikes..

Q: When you talk about restraining plants do you think that relates to your ideas about how society makes plants ornamental in cities?

Yes, in a way. Doing this piece, I tried to reproduce Art Nouveau decorative shapes and made plastic plants covered in white, shining paint follow them.

I took interest in Art Nouveau because I liked its shapes, but also because it was happening at the same time as industrialization of the cities. It’s really interesting to see how folklore around plants and their ornamental qualities were used in Art Nouveau design to decorate interiors and exteriors—almost to compensate for how the city became more complicated to live in and more polluted, noisy with factories—though I may be a bit caricatural about that period. As maybe plants became more absent from cities, they were used as a symbol of comfort; their representation functioned as a layer of makeup, a way to make urban space more attractive.

I had these stories in mind while making Be My Tutor.

7. Do you see yourself staying in Paris long-term, or are there other cities that inspire you to work there?

Actually, I'm going to Japan in two months. I will work in Tokyo for six months, and I feel like it's going to be an inspiring experience.

In the long term, it's an idea I’m not really sure about. Maybe I'd like to create or take part in a collective studio structure farther from Paris in the future.

8. What would you like to accomplish in the next few years?

I'd just love to be able to continue my practice, to participate in residencies—maybe in a rural environment.

I'd also like to make a collection of poems or some sort of edition. I keep most of my poems private—but I’d really like finding a form for them to exist in another way and be shared.

9. If there’s one thing you hope people take away from your work, what would it be?

It's really simple, but emotions or feelings. I’d also like it if people wanted to touch my pieces. Most of the pieces I feel attracted to, I really want to touch; I see it as a kind of sign.

I think visual pleasure, and a certain degree of detail you can feel appealed to and look at for a moment, are important things for me.

Q: What emotions do you experience when you look at your work?

I feel like my work has a kind of gentleness in the forms and colors, and that's something I'm really happy about. At the same time, I can feel some sort of underlying tension looking at some pieces.